Instructional theory

This section of the Flight Instructor Guide supports the Instructional Techniques Course required for an instructor rating.

The expert flight instructor is master of many skills and fields of knowledge. What is taught demands technical competence in these areas, but how the teaching is accomplished depends on your understanding of how people learn and the ability to apply that understanding. The following gives some insights into the learning process and is meant to guide you into areas of further study. Teaching is a rewarding experience, but those rewards are not easily achieved. It is doubtful that anyone has a natural ability to teach or understand how others learn, therefore the professional instructor continues the life-long process of learning not only flying skills but also teaching skills.

It is intended that this section be reviewed regularly so that you gain the most benefit from it. As your experience widens, you will need to draw on a wider and wider variety of teaching methods so that you can maximise your student's learning. Refreshing this section should help you remember those teaching methods that you may not use very often.

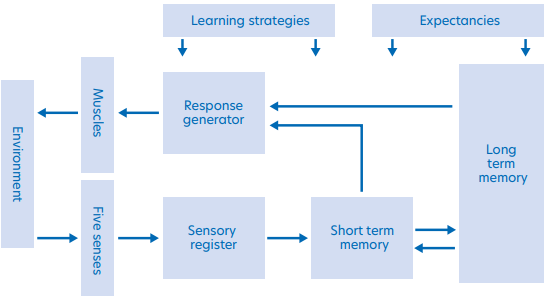

To understand how a person learns, we first need to consider a basic model of information processing1 (see diagram below).

Figure 1 Information processing

The five senses are acted on by the environment (the cockpit, classroom or instructor) and the information is passed by the nervous system to the sensory register. The information remains in its original form for only a fraction of a second while pattern recognition takes place, giving form and shape to the information.

The information passed to the short-term or working memory, is coded as a concept. For example, the word aeroplane takes on meaning, but information received from long-term memory may modify that concept, say to a jet aeroplane. This re-coded information is passed to long-term memory for storage or is acted on.

Information from either short-term or long-term memory is passed to the response generator, or decision-maker, and this information is passed through the nervous system to the body's muscles, which act on the environment.

This whole process is affected by expectancies. For example, you will probably have had an experience of seeing what you wanted to see, rather than what was actually there. Expectancies affect the way information is perceived, the way it is coded, and the generated response.

The process is further affected by the strategies used to encode the information - learning strategies2. For example, the use of mnemonics or mind-mapping to store information can greatly affect later retrieval.

To define learning, it is necessary to analyse what happens to the individual. As a result of a learning experience, an individual's way of perceiving, thinking, feeling and doing may change. Therefore, learning can be defined as "a change in behaviour as a result of experience that persists"1. The behaviour can be physical and overt, or it can be intellectual or attitudinal, and therefore not easily seen. Learning occurs continuously throughout a person's lifetime.

The student can only learn from individual experience. A person's knowledge is a result of experience, and no two people have had identical experiences. Even when observing the same event, two people react differently; they learn different things from it, according to the manner in which the situation affects their individual needs. Previous experience conditions a person to respond to some things and ignore others.

All learning is by experience3, but it takes place in different forms and in varying degrees. Some experiences involve the whole person, while others only the ears and memory. You are faced with the problem of providing experiences that are meaningful, varied and appropriate; for example, by repeated drill, students can learn to say a list of words, or by rote they can learn to recite certain principles of flight. However, they can only make them meaningful if they understand them well enough to apply them correctly to real situations. If an experience challenges the learner, requires involvement with feelings, thoughts, memory of past experiences, and physical activity, it is more effective than an experience in which all the learner has to do is commit something to memory2.

It seems clear enough that the learning of a physical piloting skill requires experience in performing that skill. However, mental habits are also learned through practice. If students are to use sound judgement and solve problems well, they must have had learning experiences in which they have exercised judgement and applied their knowledge of general principles in the solving of realistic problems4.

Each student sees a learning situation from a different viewpoint. Each student's past experience affects readiness to learn. Most people have fairly definite ideas about what they want to achieve. Therefore, each student has specific goals and their needs and attitudes may determine what they learn as much as what you are trying to get them to learn. Students learn from any activity that tends to further their goals. The effective instructor must discover the student's goals and seek ways to relate new learning to those goals1.

If instructors see their objective as being only to train their student's memory and muscles, they underestimate the potential of the teaching situation. Students may learn much that you did not intend, for they did not leave their thinking minds or feelings at home, just because these were not included in your lesson plan. Learning can be classified by type as: verbal, conceptual, perceptual, motor, problem solving and emotional. These divisions are artificial, however. For example, a class learning problem solving may learn by trying to solve real problems. In doing so it is also engaged in verbal learning and sensory perception. Each student approaches the task with preconceived ideas and feelings, and for many students these ideas change as a result of the experience. The learning process, therefore, may include many types of learning, all taking place at the same time.

In another sense, while learning the subject at hand, students may be learning other things as well. They may be developing attitudes about aviation, good or bad, depending on what they experience. You must always display a professional attitude, regardless of whether or not instruction is actually taking place. This learning is sometimes called incidental5, but it may have a great impact on the total development of the student.

You cannot assume that students remember something just because they were present in the classroom, briefing or aircraft when you taught it. Neither can you assume that the students can apply what they know because they can quote the correct answer from the book. For the students to learn, they must attend to instruction, react and respond by relating information to their knowledge and experience, construct meaning from that interaction, and attribute results to their own effort2. If learning is a process of changing behaviour, that process must be inter-active and observable.