Here’s a heads-up to the pilots of light aircraft. It can take minutes for the air to settle in the wake of some helicopters.

The disturbed air behind a large, slowly taxiing, or hovering helicopter, can be as formidably dangerous as that behind a medium-sized passenger aircraft.

“Helicopters in New Zealand have become heavier over the years,” says CAA Safety Investigator David Oliver (ATPL-H). “This is just part of the aviation sector becoming more professional – those heavier helicopters are generally more capable.”

But the extra mass means the disturbed air those heavier aircraft leave in their wake is more severe and lasts longer.

“Pilots of light aircraft need to be hyper-aware of any helicopter operating in the vicinity, and to give rotary aircraft a good couple of minutes after they’ve gone ahead or passed by, before continuing to operate,” says David.

CAA Flight Examiner (H) Andy McKay says helicopters may hover taxi across an active runway with fixed-wing traffic on final.

“This presents an active risk, as the wake turbulence may affect the aircraft at a crucial stage in the low-speed round out. The heavier the helicopter, the greater the risk of a loss of control.”

Andy says that because fixed-wing and rotary aircraft often operate from common holding points or taxiways, flight instructors have a responsibility to educate students of the risks, early in training.

“Because if this guidance is left until the later stages of training, students are oblivious to the immediate danger of fixed-wing and helicopters operating in close proximity.”

What fixed-wing pilots can do to keep themselves safe

Communicate with the helicopter pilot, letting them know of your intentions, and actively listen when they state theirs.

Be patient. FAA studies indicate the disturbance created by a heavy-ish helicopter can affect the air for up to three minutes.

Park well away from an obvious helicopter movement area, Jet A1 fuel pump, or helicopter hangar. Smaller aircraft parked next to a helicopter hangar have been blown over by the downwash when the helicopter manoeuvres to its home pad.

Slow hover taxi or stationary hover

Fly at a distance of at least three times the diameter of a helicopter’s rotors. Source: FAA

Be aware of wind direction. Wake vortices created by the helicopter can be driven towards another aircraft by even a slight crosswind.

Fly at a distance of at least three times the diameter of a helicopter’s rotors in a slow hover taxi or stationary hover.

Think ahead. If a fixed-wing aircraft finds itself in a sudden and unexpected wobble due to wake turbulence, the chances are that it will be at extremely low-level.

“Taking immediate action, however, is vital,” says CAA Flight Operations Inspector Terry Curtis (ATPL-A). “You need to execute a swift go-around.

“Getting entangled with rotary wake turbulence is a frightening experience, even if it’s happened before, so you need to be proactive in avoiding this stuff.

“You need to maintain great situational awareness, looking out and around for helicopters, particularly if they are operating at slow speeds, particularly if they’re large-ish, and particularly if they’re two-bladed. All these factors contribute to a more severe wake effect.”

What rotary pilots can do to keep other pilots safe

Communicate with fixed-wing pilots, letting them know of your intentions, actively listening when they state theirs.

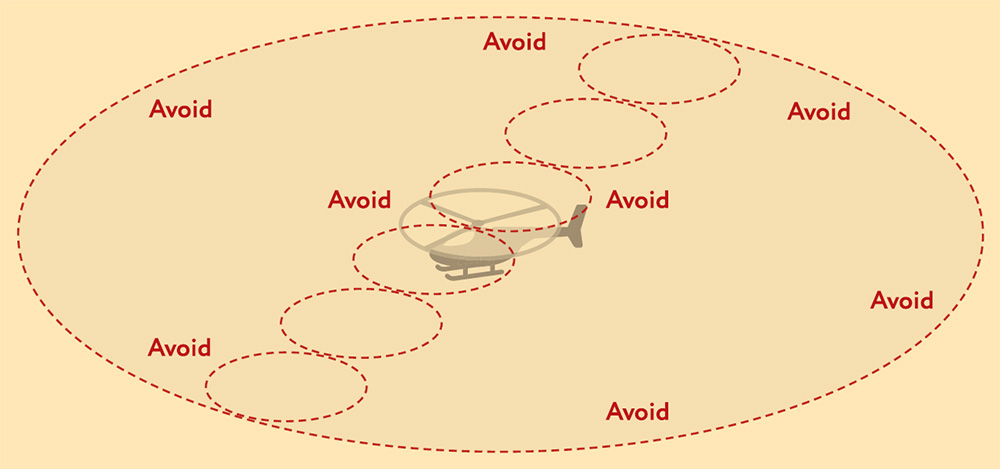

When rotor downwash hits the ground surface, the vortex circulation is outward, upward, around, and away from the main rotors in all directions. Be aware of where aircraft are, the wind, and its effect on that downwash.

Fly a set – and therefore predictable – path to the FATO (final approach and take-off area) then hover taxi or ground taxi to where you need to be.

Image credit: iStock.com/kruwt