When it comes to human factors, the research has historically focused on pilots. That’s probably not surprising given they sit at the ‘sharp end’.

But time, and research, has shown us that pilot error isn’t the only cause of fatal accidents. Human error anywhere in the aviation system can lead to catastrophic consequences. It’s important for all aviation participants to understand what human factors are, why errors occur and how we can try to prevent them.

How would you cope if an error you made ended in a fatal accident? We usually only think of the victims of an accident as those who are injured, or who die. But where that accident was caused by someone else’s error, we have what is known in human factors circles as a ‘second victim’.

A second victim is a person who’s involved in a serious incident or accident and who feels personally responsible for what happened. Aircraft maintenance engineering is one obvious role where this could apply. And that’s why this human factors information is not just for pilots. It’s for anyone who participates in aviation and whose decisions and actions can affect the ‘sharp end’.

As a society, we tend to blame such professionals who may be involved in serious incidents and accidents, assuming that because they weren’t hurt, they’re not a victim. But this is short-sighted and fails to understand the traumatic experience of being the one whose error led to such a consequential outcome.

Your awareness of how your decisions and actions are influenced by human factors may just prevent you from ending up a second victim.

Photo: iStock/Alina555

We’ve created this section, dedicated to presenting human factors information in the maintenance engineering context, because this role is integral to the safety of the aviation system. This doesn’t mean the information in all the other sections isn’t relevant, and we encourage engineers to read all of it.

But in this section, you’ll find information and links to other resources specific to your profession, without having to wade through pilot-centric stuff to find it.

Maintenance is a vital element of a reliable, sustainable, and safe aviation system so it’s critical that maintenance engineers, managers, and organisations take an active interest in understanding why humans make mistakes.

The two videos below are produced by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia (CASA). The first video provides a fictitious example of an organisation with poor safety management practices. The second video provides ‘best practice’ examples for better standards of safety in the maintenance environment.

Maintenance engineers don’t turn up to work intending to do a poor job. But there are literally hundreds of factors that can lead to unintentional errors. These errors can then lead to catastrophic consequences. The following CASA video highlights why it’s important that we understand these factors that can lead to error, and to manage them effectively through an organisation’s Safety Management System.

Research into maintenance human factors has identified what is often referred to as the ‘Dirty Dozen’. These are the most common factors contributing to maintenance errors. Click the drop-down menus below to learn more about each factor and the countermeasures engineers and maintenance organisations can use to prevent errors.

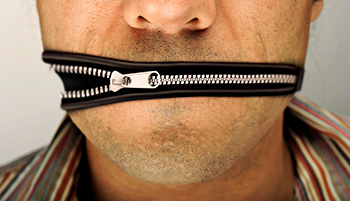

Communication takes the number one spot on the Dirty Dozen list. And that’s because it’s one of the main contributors to serious incidents and accidents. To draw on a quote from author George Bernard Shaw:

“The single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

Photo: iStock/EvgeniyShkolenko

We all need to become skilled in how to convey our ideas, listen, hear, give feedback, not interrupt, ask meaningful questions, and how to have difficult conversations. These skills are useful in everyday life, but in a safety-critical environment such as a maintenance hangar, they can mean the difference between life and death.

Communication is a process between a ‘transmitter’ and a ‘receiver’ and involves a ‘method of transmission’. A lot of things can interfere at any of these three levels. Ambiguous instructions, assumptions, attentional focus of the receiver, or tone of the transmitter are all examples of things that can cause breakdowns in communication. When communication is verbal, studies show that only around 30 percent of a message is received and understood!

What countermeasures will help us communicate well?

A distraction is anything taking our attention away from the task at hand. Some distractions are unavoidable, such as noise or requests for help from others.

Photo: iStock/EvgeniyShkolenko

Some distractions may actually be providing us with valuable information that needs to be considered as part of our current task. And yet other distractions, such as phone calls and text messages, social conversations, or administrative work simply drag our attention elsewhere.

Psychologists say that distractions are the number one reason we forget things, but we can’t eliminate or avoid all distractions, so we need to manage them effectively.

What countermeasures will help us effectively manage distractions?

What can organisations do to reduce distractions in the workplace?

Photo: iStock/mediaphotos

If we don’t have enough resources, we may either not be able to complete a task or it may end in a low-quality result. When we talk about ‘resources’ we’re referring to a multitude of things – personnel, time, data, tools, parts, skills, experience, and knowledge. Not having enough of these things interferes with our ability to complete our work.

What countermeasures will help?

Stress occurs in two forms:

Photo: iStock/Jane-jud

Signs of long-term stress include sleep issues, digestive issues, mood problems, increased errors, and an inability to concentrate or remember things.

Stress is always a part of maintenance engineers’ lives. Flight delays or cancellations with aircraft requiring immediate attention, or pressure to complete scheduled maintenance on time, are ever-present.

What countermeasures can help to reduce stress?

Photo: iStock/choja

Complacency is a sense of self-satisfaction that tends to accompany growing confidence and experience. It creeps in particularly with routine tasks. Complacency can lead us to have decreased awareness of potential dangers, and to miss important signals. It can affect individuals or entire organisations. If you’re working on something you consider ‘easy’ or ‘safe’, then you’re more likely to fall into the complacency trap, especially if you’re working from memory and not using a checklist. A maintenance engineer might neglect or skip tasks, such as inspections, for example, if there’s a misconception that an inspection task is not essential.

What countermeasures can reduce the trap of complacency?

Photo: iStock/DNY59

Being an effective team requires skills in leadership, ‘followership’, communication, trust-building, motivation of yourself and others, and the ability to give or receive effective feedback. Ineffective teamwork can affect safety so it’s important in safety-critical industries like aviation, that how to build effective teams is understood by everyone.

Key things helping build an effective team are:

Photo: iStock/triloks

Working under pressure is common in a dynamic aviation industry. It may be time pressure – perhaps you need to get an aircraft operational and back online as soon as possible to minimise schedule disruptions.

It may be pressure from a client – they’re planning to head off for the weekend and it’s taking longer than expected to finish inspecting their aircraft.

It may be that we’re operating with reduced staffing levels and fewer people are trying to cover more work. But sometimes, the pressure is self-imposed – taking on more work than we can handle, trying to be the ‘can do’ employee, or feeling a sense of responsibility to get the job done. Pressure, whatever its source, can cause us to give tasks less attention than necessary, skip tasks, or reach a point where we feel we just can’t cope.

What countermeasures can we take?

Photo: iStock/sturti

Working safely in a maintenance environment requires everyone to have ‘the big picture’. Working in isolation and considering only your own responsibilities can lead to tunnel vision and reduced awareness of how your actions may be affecting others, and the wider job. Reduced awareness can occur because of individual stress, fatigue, pressure, or distraction.

So having a broad understanding of the entire ‘Dirty Dozen’ is necessary so that you understand how each of the factors can interact with the others.

To maintain safety in a maintenance environment it’s essential to be aware of what’s going on around us. Vigilance is closely related to situational awareness, and we can maintain our attention by following workplace procedures.

What countermeasures can we take to increase our awareness?

Photo: iStock/Professor25

A lot of roles in aviation are highly technical, requiring comprehensive and lengthy training. Aircraft systems are complex with ever-evolving technologies. Keeping up with the required knowledge needs ongoing professional development and on-the-job experience. A lack of knowledge can lead to maintenance engineers misjudging situations and making unsafe decisions.

What countermeasures can we take?

Photo: iStock/monkeybusinessimages

Fatigue can arise from having had a poor sleep, or several successive poor sleeps. It can occur because we work a late, or night, shift and we’re awake when our bodies are meant to be asleep. When working through the night, the catch-up sleep we get during the day is generally not of the same quality as the sleep we get at night. Fatigue can also arise from ongoing stress either in our work or personal lives.

Fatigue affects different parts of the brain in different ways. Guess which part is one of the worst for suffering the effects of fatigue? It’s the part of our brain, tucked neatly into our foreheads, that we use to make decisions. It’s called the pre-frontal cortex. So it’s not surprising to find that our decision-making abilities become much poorer when we are fatigued.

Even simple decision-making can be harder, but the kinds of complex decisions we might have to make in the uncertain environment of aviation are at high risk of involving error if we’re fatigued. Maintenance engineers are often rostered at hours that are less than optimal for humans. This is why aviation operators are required to have fatigue risk management plans in place to mitigate the serious risks to aviation safety that fatigue can pose. All professionals in an aviation environment need to actively consider IMSAFE principles when deciding whether they are fit to go to work on any given day.

Fatigue can have serious implications for aviation safety and because it’s so important, you’ll find a whole section on fatigue and managing it.

What countermeasures can we take?

Photo: iStock/Inkout

As with any industry, aviation is made up of a broad range of personalities with differing strengths and weaknesses. When it comes to assertiveness, every person will differ in their capacity to use this particular skill. Assertiveness is a necessary skill in aviation because it improves communication, allowing us to express our feelings, opinions, concerns, or needs positively and productively.

It allows us to communicate directly, honestly, and respectfully. Struggling to be assertive can lead to us failing to communicate and that can have fatal consequences.

Unassertive team members may not challenge decisions or ideas that may be wrong or dangerous. Worse still is an overbearing colleague who doesn’t allow others to express themselves, increasing the possibility of error.

What countermeasures can we take?

Photo: iStock/thelinke

Have you ever heard someone say, ‘This is the way we do things here’..? If so, that should set your alarm bells ringing. It doesn’t necessarily mean that things are done badly, but you need to be very wary of workplace cultures that may have been influenced over time, in potentially unsafe ways. Behaviours deviating from the rules or procedures, can become ingrained through peer pressure and force of habit – and become ‘norms’ that could lead to fatal consequences.

What countermeasures can we take?

The ‘dirty dozen’ don’t occur in isolation, and the following video, produced by CASA, provides an example of how the interaction of some of these factors can contribute to unsafe maintenance outcomes. There’s a lot to consider when it comes to operating safely as a maintenance engineer, so take the time to reflect on the information and video’s provided on this page. Are you taking the steps necessary to ensure you’re operating as safely as you can?

Human factors resource guide for engineers (CASA)(external link)

If you have any questions about this topic, email humanfactors@caa.govt.nz