Don’t allow a once-over-lightly duplicate inspection in your workshop endanger your aircraft and pilots – and their passengers.

The August 2024 occurrence report filed with the CAA is stark in its description.

Prior to lifting to the hover, a lack of controlability around the ‘yaw’ axis was noticed as [the] aircraft skidded about 10 degrees nose left prior to the aircraft lifting off the ground.

The aircraft was shut down and referred to engineering for investigation. Initial investigation revealed that [the] tail rotor control rod joint was not fully engaged.

The subsequent CAA investigation found that the organisation had not ensured that the engineer was experienced in how to complete the task. It also found that a breakdown in duplicate inspection procedures contributed to the incident.

There are duplicate inspections – and there are duplicate inspections

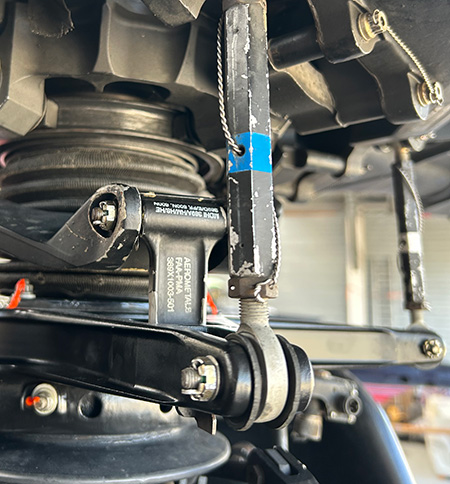

Photo courtesy of Russell Keast.

When an ineffective duplicate inspection is carried out, the effects are insidious, because the pilot may not be able to detect any possible issue in their preflight check.

Because of this, and that a potential system failure is so obviously dangerous, Part 43 General Maintenance Rules requires the maintenance of control systems be double-checked before the aircraft is released to service.

CAA Aviation Safety Advisor Richard Lane – 35+ years in engineering, and a PPL-holder – says the incident described at the start of this article is one of four in New Zealand that he knows of over the last six months of 2024.

“In all cases it was not an instance of the duplicate inspections not being done – they all were. It’s that the inspection failed to identify issues in one or more of the critical elements required to be checked during the duplicate inspection.”

The pre-formatted return-to-service statement outlines what must happen for a duplicate inspection to be properly robust.

We certify that a duplicate safety inspection has been carried out and the identified control system of the aircraft/component functions correctly, and in respect of the maintenance performed, the control system is assembled and locked correctly.

Refer rule 43.113(c)(3).

“Each system requires individual attention to check the correct assembly, locking, and function of that system, in accordance with the appropriate maintenance manual(s),” says Richard.

“It takes only one of these three elements to have been done incorrectly for a system failure to occur.”

CAA Aviation Safety Advisor John Keyzer – 25 years’ experience as a LAME – says that of the four recent incidents, the most potentially catastrophic happened in the South Island mid-way through 2024.

“After maintenance, and on a repositioning flight, the pilot began to notice a vibration in the helicopter. He immediately began a descent to lose as much altitude as possible.

“On getting close to the ground and, at the same time as a flight control input, there was a disconnect in the control system, resulting in a loss of aircraft control and a serious accident. The pilot was okay, but the helicopter was destroyed.”

John’s advice, in the Winter 2022 Vector article, Duplicate inspections, is that if staffing levels allow, there should be two independent inspections following assembly or adjustment of a control system.

“That is, that the first or second part of the duplicate is not carried out by the same person performing the task.”

Confirmation bias and complacency – enemies #1 and #2

CAA Chief Advisor of Human Factors, Alaska White, says that duplicates aren’t any old task to tick off the to-do list as quickly as possible to get the aircraft out the door.

“No two situations are the same, so don’t use past successes to assume everything will work out okay in the future.

“Every duplicate inspection should be carried out with healthy scepticism about whether it’s been done correctly.

“If we go in anticipating the maintenance has been done correctly, our eyes and brain will confirm that. This is called confirmation bias1, and it can be very powerful in persuading us that all is fine.”

John Keyzer says the second part of a duplicate inspection should be seen as the last opportunity to ensure that everything is correct, rather than a quick check that the first inspection has got it right.

“It’s for this reason that it can be a good idea to see the duplicate inspection as a separate activity, rather than a cursory glance associated with the carrying out of maintenance.”

Distraction – enemy #3

MDHI 369 main rotor swashplate assembly, including drive link. Photo: CAA

“Distractions are everywhere,” says Alaska White. “And countering them is not just about turning cellphones off inside the hangar.

“Make sure there are clear comms to staff and clients ahead of time, and signs to ward off unwanted or unplanned visitors who could disrupt the engineers.”

Alaska says the environment in which a duplicate inspection takes place can greatly contribute to its success – or greatly damage it.

“Duplicates require high mental workload and are demanding of attention, so engineers undertaking the duplicate need to be well-rested, in a headspace and working in an environment that enables them to perform the duplicate inspection thoroughly.

“This includes using checklists, having realistic time frames to alleviate pressure and stress, and ensuring the working environment is a comfortable climate, and has sufficient lighting and adequate tools and equipment to carry out the task.”

Practical advice

Russell Keast, Base Manager at Skywork Helicopters, has a simple but effective method to ensure distraction does not later result in an incident – or worse.

“We use fluorescent pink ribbon as an integral tool in maintaining an aircraft. The roll of tape sits in my toolbox, along with the torque wrench and my spanners.

“It’s sitting there, nice and bright, and when I look down at the tray, it’s glaringly obvious it’s there to be used.

“I tear off a long strip and tie it around the item that needs checking. My part of the job is not finished until that pink ribbon is secured. Then I’ll move on to the next task, and ‘pink ribbon’ that, and so on. “Then the second engineer does the duplicate check, and only afterwards, removes the ribbon.”

Photo courtesy of Kāpiti Districts Aero Club.

DID YOU KNOW...

… that rule 43.113 also applies to the removal and refitting of dual flight controls?

Many small aircraft may be operated with either single or dual controls for the purpose of providing flight instruction. For convenience, manufacturers often provide a ‘quick release’ mechanism to permit removal and installation of the secondary controls, when a passenger seat is to be occupied, for example.

To avoid the requirement for special tools, there can be a variety of mechanisms designed for this purpose, as well as instructions provided in the aircraft flight manual on how to carry out the task.

Regardless, the rule still applies. It’s still the removal or installation of a flight control, which could result in a flight hazard. The hazard of incorrect assembly is the most obvious. If not locked in place the control could come loose at a critical moment such as the instructor correcting their student’s stall recovery. (Imagine their surprise!).

For this reason, the duplicate inspection requirements of 43.113 apply whenever you disturb the aircraft’s controls, (including dual flight controls secured in place with quick release fasteners).

So how do you comply and stay safe?

43.113(a) requires:

- a person releasing an aircraft to service after maintenance that has involved the disturbance of any control system must ensure that a duplicate safety inspection has been carried out. (Also see Part 1 for definition of ‘maintenance’).

Who can do this?

43.113(b) states that:

- the first part of a duplicate safety inspection can be carried out only by a person who meets the requirement in rule 43.101 to certify the aircraft or component for release-to-service.

The second part of the duplicate inspection must be carried out by another person who has adequate training, knowledge and experience to carry out the safety inspection, and who is a LAME, or holds one of the following:

- a maintenance approval issued in accordance with Part 66

- a current pilot licence with a rating on the aircraft type

- an authorisation issued by the holder of a maintenance organisation certificated under Part 145

- a person issued with an engineer’s licence or approval under the authority of an ICAO contracting state

- for gliders, a current glider pilot certificate or an engineer’s approval issued by a gliding organisation.

The CAA says…

Photo: CAA

The CAA’s Chief Advisor of Airworthiness, Warren Hadfield, says that maintenance worksheets play a critical role in making sure that control system maintenance is completed correctly.

“When a control system is disturbed, an open entry should be raised in the relevant maintenance worksheet detailing the scope of control system disturbed, and referencing the requirement for a duplicate inspection.

“Whereas correct functioning requires oversight of the full control system, the inspection for correct assembly and locking should focus specifically on the sections of the control system which have been disturbed.”

Russell tells other staff when he’s about to do a duplicate inspection, and they know not to interrupt him. The office staff know not to forward calls to him. His cellphone stays outside.

“If you’re the chief engineer or senior engineer, and you have someone waiting to be paid, and the boss turns up, and there’s a phone call for you, and the pilot turns up asking why things are taking so long, it’s hard not to be distracted. It takes real discipline.

“But if you really do have to stop to attend to something else, the pink ribbon will remind you that you haven’t completed the task – because the duplicate hasn’t been done.”

Russell offers this further tip. “We use a duplicate inspection checklist for each ‘zone’ of the aircraft. We have one sheet each for the airframe, engine, main rotor area, and for the tail. I know some engineers note all their duplicate inspections on the one checklist sheet, but I think that’s too many.”

Skywork also uses ‘maintenance in progress’ flags attached to the helicopter tail.

“They’re a visual indication to pilots that the helicopter has not yet been released to service,” says Russell.

“This is especially important when maintenance is being done at an operational base with multiple helicopters and pilots present.

“If I get hit by a bus on my way home, the others here need to know exactly where I was in the process. These simple indicators really help.”

Now check out...

Drifting away from safety, by CAA Chief Advisor of Human Factors Alaska White in Vector (Winter 2023).

Duplicate inspections, Vector (Winter 2022).

Footnote

1 We pay attention mainly to information confirming our expectations, and we ignore, or don’t see, or minimise, information which doesn’t.